Hello, everyone! Today I’ll be answering a question on a topic I am very passionate about: what is food insecurity?

If you were to ask me where I see myself being in twenty years, I would say that I’d be working with the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations, fighting for greater food security and eradicating malnourishment around the world. In addition, I would like to redesign the Westernized food system to minimize food waste. Maybe it’ll take more than twenty years to get to this point, maybe less, but that’s what I see myself doing at some point in my future. To get to this place, I’ve already started my journey by educating myself on the current issues around the world, as well as sharing my knowledge with all of you!

I hope you learn a thing or two from this post. It’s a very serious topic, and there are some interesting facts that I think many of you may not have considered or realized before. Dealing with the issue of food insecurity requires action from everyone, even you and I. You may not see how we can be of help just yet, but I’ll explain that all in the post.

What is food insecurity?

Food security is not just about food. It’s about people and relationships. At the 1996 World Food Summit in Rome, food security was defined and then revised to the following statement:

Food security, at the individual, household, national, regional and global levels [is achieved] when all people, at all times, have physical and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food to meet their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life.

FAO, 2001 Tweet

Who does food insecurity affect?

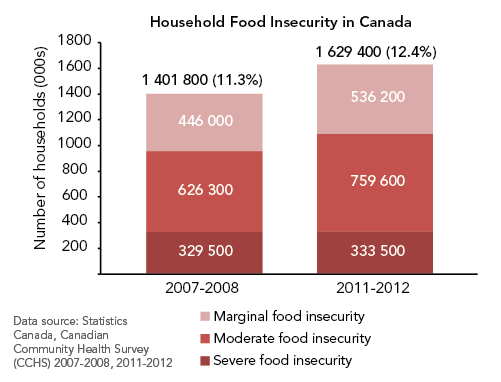

Food insecurity affects 1 in 8 Canadian households. There are three types of food insecurity: marginal food insecurity, where a household worries about having limited access to food or worry about running out; moderate food insecurity, where households must compromise the amount of food or the quality of food that they supply to their household; and severe food insecurity, where members of or entire households miss meals and experience an overall reduction in the amount of food they are able to consume.

In all types of food security, it’s about more than just having enough food. Note the use of the words “access,” “safe” and “nutritious” in the FAO’s definition. Focusing on the latter of these, someone who does not receive enough nutrients in their diet can be considered undernourished or malnourished. Undernourishment usually refers to a diet providing too little energy and doesn’t necessarily consider inadequate nutrient intake. Malnourishment is a result of the deficiency of essential nutrients needed for a healthy functioning body. To clarify, nutrients include things like vitamins (A, B, C, D, E, K), minerals (calcium, iron, zinc, etc.) as well as the macronutrients (carbs, fat and protein) and water. The body needs all of these nutrients in various combinations; compromising the balance of nutrients in the body can have serious effects on our health. The FAO considers malnourishment to be a “triple burden,”as it can result in child stunting (lower growth-to-age ratio), micronutrient deficiencies and adult obesity (yes, you heard me right on that one—more on that shortly.

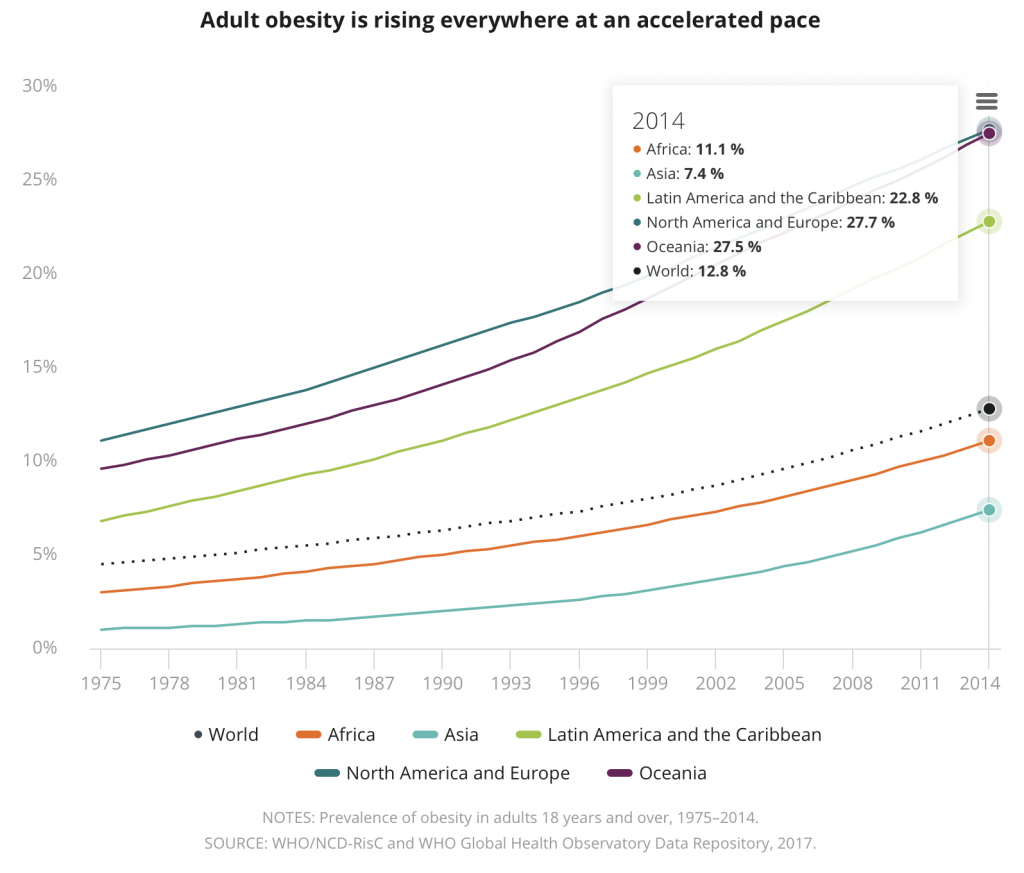

Surprisingly, many malnourished people are not at an energy deficit. In 2014, 42 million children worldwide were overweight or obese while 156 million children experienced stunted growth as a result of inadequate nutrient intake. Inadequate nutrition, whether a child is obese or severely underweight, is causing half of the deaths in children in developing countries. The rates of obesity are still on the rise, potentially attributing to more of these deaths in the future. In other words, illness and death resulting from poor nutrition is a problem that won’t be going away any time in the near future, and it impacts every country in the world, regardless of their economic status.

North america: the energy-nutrient divide

In North America, we have a lot of food. This food is typically energy dense, but not nutrient dense. Energy dense foods provide you with a lot of energy, or calories. Nutrient dense foods provide you with a lot of nutrients, like vitamins and minerals. So, while something like a Big Mac and large fries may be full of energy (which, yes, you do need as well), their nutrient profiles are quite limited and cannot provide you with all the nutrients your body needs to function well.

What are some nutrient dense foods? Think whole grains, fresh fruits and vegetables, all things we have easy access to here in North America and take for granted. To produce foods that provide so much goodness for us, they require a considerable amount of energy (this time I’m talking about electrical and mechanical energy invested in producing the food) and time to produce. In addition, most of these foods have very specific growing conditions, which can complicate the growing process even further. Since so much must be invested in producing these foods, by the time they arrive at our grocery stores they can be quite expensive.

Think about a low-income family. The caregivers may be working hard at their minimum wage jobs all day to provide for their family. Growing kids and teens eat a lot of food, not to mention go through so many clothes and toys as they age. The parents want to provide their kids with three meals a day every day, but doing so on a low income can be challenging. To provide their kids (and themselves, for that matter) with enough energy they need every day, chances are they’ll be reaching for the prepackaged cereals, the microwave meals and making trips to fast food restaurants. These energy dense foods are much cheaper than the organic avocado and fresh fruit smoothie. The sad thing about this is that by trying to support their children as best they can, the lack of variety and fresh foods in their diet can impact them in serious ways, causing more health problems down the road.

Source: Huffington Post

This is a problem all around the world now, yet most nutrient deficiencies that occur as a result of “cheap” diets go undiscovered. This is often because malnourishment is masked by other “problems,” such as obesity (side note: while the health of some individuals suffers from being in a larger body, others are naturally meant to be that size and are totally healthy!). If an individual is obese or “overweight” because they provide too much energy for their body but aren’t providing enough nutrients to support things like their metabolic, neurological and digestive systems, the nutrient deficiency can be overlooked because all people see is the “too much”part and not the “not enough” part of the problem.

Mexico: a case study

Traditionally, Mexico has been a strong, agriculturally rich country which could provide their citizens with sufficient, nutrient-dense foods. In 1994, NAFTA (North American Free Trade Agreement) was signed, promising more jobs and a stronger economy by increasing trade between Canada, the United States and Mexico.

In the desire to grow economically, Mexico started exporting their fruit and vegetable crops more and more. Very quickly the nation started cracking against the intense pressure of the market’s demands for their crops. Mexico was once home to many small farms, but as the international demand for their crops grew, a sacrifice had to be made and the citizens of Mexico got less and less access to their own crops. Many of their small farms couldn’t keep up with demands and had to shut down; the farmers, desperate for work, moved into the rapidly-industrializing cities, destroying their strong communities that revolved around their food culture.

At the same time, NAFTA allowed cheap foods to be exported to Mexico from the States without charging them tariffs (taxes). This created an influx of fast food into the struggling nation while the States exploded economically. Poor quality “convenience foods” like chips, candy and soda were imported at accelerating rates, filling the expanding cities. Today, this cheap food overwhelms Mexico’s population, smothering the country’s cultural food system even more. The 2008 recession worsened Mexico’s financial situation, putting even more farmers out of business and forcing them into the “junk” food-rich cities.

You can imagine the impact on one’s health and wellbeing from living in a poor economic state with an abundant access to cheap, greasy foods. In 2013, the FAO reported that 32.8 percent of adults in Mexico were obese; the percent of obese adults in America was 31.8, marking Mexico as the country with the largest percent of its population being obese in the world. Clearly, Mexico is facing a crisis with food insecurity, yet all people see are these obesity rates.

After this report, the country tried to take reclaim the health, or rather the “weight” of its population. In 2014, Mexico introduced an 8 percent tax on junk foods. A study from PLOS Medicine observed there to be a 5.1 percent reduction in junk food purchases within the first year of introducing the tax, more so in low to middle-income households than high income households. However, the study does not indicate whether these households purchased more produce or nutrient-dense foods, or if they even replaced said purchases at all and have since reduced their food intake. Despite introducing this tax in attempts to reduce the rising obesity rates in the country, the unforeseen consequences on the poor’s ability to supply for their families may become a larger problem. Increasing the price of the only foods accessible to the population won’t help them gain more access to nutrient-dense foods.It just means that they have even fewer options to provide their families with.

For a population like Mexico’s that relies on cheap, nutrient-poor foods, obesity and malnutrition rates are rising simultaneously. While it might seem all fine and dandy because Mexico’s all-season crops are in such high demand in off-season countries like Canada and the States, local farms and rural communities are shutting down, losing their culture – which largely revolves around food – and have no choice but to live in poverty-stricken cities, where obesity and malnourishment go hand in hand, often in the same household. Crazy, right? This fact has been recognized by the FAO, whom stated “when resources for food become scarce, and people’s means to access nutritious food diminish, they often rely on less-healthy, more energy-dense food choices that can lead to overweight and obesity.”

Not surprisingly, the FAO also found that the triple burden of malnourishment rises as urbanization increases, because separating the consumers from the producers strips away community culture and forces people into dense, unhealthy cities. Mexico is a perfect example of this, as are other countries facing rapid industrialization and transitioning from rural to urban settings. The greater the urbanization, the more detached communities become from their culture and their native land. In every culture, food plays a huge role. It’s how people connect. Sharing stories around the dinner table, parents passing down recipes to their children throughout generations, tending to the agricultural land that’s been in families for centuries; the connection we have with our food has essential for our culture and values for thousands of years, but only recently this connection has started to fade as we become a society obsessed with the cheap and fast.

too much poor quality food

On the opposite end of the spectrum, we have countries who don’t have access to nutrient dense or energy dense foods. An increasing divide between the food secure and insecure exists within countries, between urban and rural areas, and even within one’s own household. On average, rural areas show greater rates of malnutrition, and areas facing regular crime, or corrupted households are at the greatest risk.

Figures released by the World Bank showed that, in 2015, of the top ten countries facing the largest percent of undernourishment in their population, seven out of ten of these countries are in Africa. Asian countries also face a great deal of undernourishment, these two continents facing the worst problems around the world. Obesity is still on the rise in these regions—it’s on the rise everywhere in the world, but the percentage of the population classified as obese is significantly lower than areas like North America or Europe. In 2014, 11.1 percent of Africa’s population and 7.4 percent of Asia’s population were classified as obese.

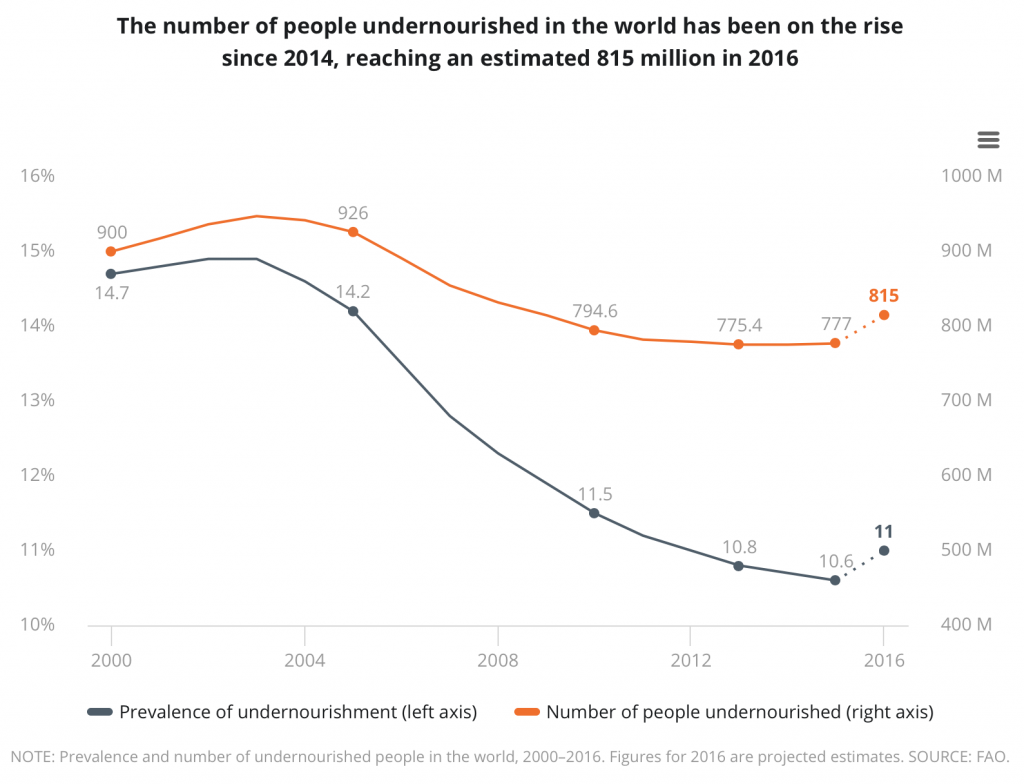

Despite the total percentage of the world’s population classified as undernourished dropped from 14.8 percent in 2000 to 10.7 in 2015, it’s still a serious problem that doesn’t appear to be going away any time soon. In fact, the FAO found that the number of undernourished in 2015 was 777 million people, but in 2017 it rose to an estimated 815 million. The situation only worsens in Sub-Saharan Africa, as well as Southeastern and Southwestern Asia, likely as a result of climate-related disasters such as El Niño and growing violence in these areas.

Food insecurity is most prevalent in marginalized regions, meaning those most susceptible to the impacts of natural hazards and conflict over resources, areas where there isn’t access or there’s unsafe access to said resources. For instance, 48 percent of civil conflict since 2000 has taken place in Africa, 90 percent of them involving their rural land that is used for agriculture.

I’ve said it so many times now, but the problem with our food system isn’t that we don’t have enough food. If we didn’t have enough food, we wouldn’t be throwing away 40 percent of our food, would we? Why do developed nations have a surplus of both fast foods and nutrient-dense foods, so much so that they’re wasting so much of it? Why are places like Mexico, which produce so many fruits and vegetables, face such high rates of obesity and malnourishment? Why do struggling regions already exposed to war and natural disaster also have to starve because they don’t have access to food? The core of the problem is the food distribution system.

In the Western world, we have no trouble going to the superstore every week to stock up on groceries, we can run to the 24-hour convenience store down the street for a snack at any time, and we can go to a restaurant or fast food place for dinner when we just don’t feel like cooking. There are so many people in the world who don’t have access to food like we do. Some of these people are fortunate if they see a fruit or vegetable in their home once a week or even once a month.

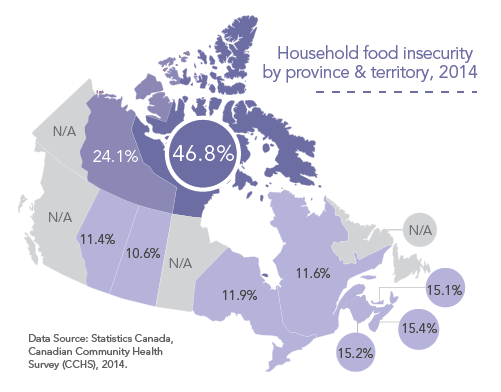

This contrast between food surplus and food scarcity is not just between continents or countries. In the 2014 Canadian Community Health Survey completed by Statistics Canada, 11.9 percent of Ontario’s households were observed to be food insecure. In Nunavut, that number was an astounding 46.8 percent.

The Nunavut Bureau of Statistics completed a study in 2017 comparing the prices of regular food items in the province to the national average. The national average price for a 2.5kg bag of white flour was $4.91; in Nunavut, the price was, on average, $13.81 for the very same bag. The national average for a whole chicken was $7.71, while in Nunavut it was $13.54. 1kg of oranges was $3.32 on average across the country, and $7.47 in Nunavut. The photos below show actual prices from one store in Nunavut: as you can see, a bottle of ketchup costs $16.79, and a 2.2lb bag of grapes cost $28.19.

You can see how difficult it would be for a family in Nunavut and similar areas to have a sufficient, proficient food supply. Remote provinces have limited access to food as it must be shipped in by planes or ships. Long transportation times inflates the price tremendously in the grocery stores, and many stores often run out of food products when extreme weather prevents the deliveries from getting through. Especially in Nunavut, one of the most northern regions of the country, their cold winters and foggy summers can prevent planes from travelling for weeks, and ships only come through a few times a year. And for a province of 38,456 people (as of April 1 2018) with an unemployment rate of 12.8 percent–the national average is 5.8 percent, by the way—this becomes a serious issue.

I did a quick look at my local grocery stores flyer and found that the same bottle of ketchup is on sale for $3.47. Doing the math, that same bottle in Nunavut is 484% more expensive. I just can’t fathom this. Considering the estimated costs of food waste in Canada alone is 31 billion dollars, the fact that so many are going undernourished really makes me question our societal values.

compromise?

Quite clearly, we have food insecurity issues within our well-off, high income country. Since overall we are seen as a “developed” and “strong” country, the marginalized communities are left unheard and often suffer for their whole lives. What’s even scarier is that this insecurity also exists in First Nations communities within Ontario. A 2014 study of First Nations people in Sub-Arctic Ontario found that 70 percent of households were food insecure, 53 percent of which facing moderate insecurity and 17 percent facing severe insecurity. Despite how well off we are here in Southern Ontario (and there are families also struggling in our area, too; think about how many homeless people there are in Toronto, for example) there are people all around us struggling. Nonetheless, we turn a blind eye and pretend everything is fine because our kitchens are fully stocked. With these prices, it’s no wonder that malnourishment is prevalent in these communities. Meanwhile, 40 percent of food in Canada is wasted annually.

Food insecurity is no simple problem that can be overcome, and thus there is no one simple solution. Food insecurity is not just about the food: there are economic, political, cultural, environmental and social factors to consider. To tackle food security, we need to approach the issue from every angle. While creating an easier transportation to isolated communities in Nunavut, there also needs to be a way to keep costs down for the foods being transported. Some communities have already come up with their own solutions to this, by investing in greenhouses and teaching their youth how to sustainably farm with their climate so they can grow their own foods, as shown at a greenhouse in Iqaluit below.

At the same time, we need to reduce the amount of food waste we create or find ways to repurpose it (like giving it to struggling communities). In Canada alone, scarce and expensive food in the northern regions contrasts our abundant, inexpensive foods here in the south. If we could find a way to divert or even discourage our waste to provide more food in these isolated regions, we can tackle both problems in one go. Of course, there are many legal, social and political concerns that arise when considering this, but I believe that getting all of the key players together to discuss the issue and COMPROMISE (key word here!) is the first step in creating an effective solution.

Areas simultaneously facing obesity and malnourishment need to prioritize the health and wellbeing of their population. While some may not think that these problems affect them, they impact everyone. For example, that CEO—let’s call him Joe—who owns a major corporation which manufactures its products in factories located in lower-income neighbourhoods? They’re affected, too. Health issues related to obesity and malnourishment can impact the performance of work done by these struggling individuals working in these factories. If Joe’s employees aren’t performing to their best abilities due to their conditions, his company suffers, and his profits go down. Not good.

What if this issue occurs not only for Joe’s company, but also Susan’s, Billy’s, Jerald’s, Nora’s and Carol’s companies? If the issue becomes prevalent enough, the overall economy of the nation and those they trade with will be impacted. Do you see the problem now? Everyone is impacted by food insecurity.

All communities deserve access to fresh, nutrient-rich and affordable foods. Making this possible isn’t that easy unfortunately. If Mexico deliberately works to decrease the stress put on their market and producers by reducing how much they export annually, more crops will be left for the native population. Access to more fresh and affordable food is a step towards decreasing the health problems facing their population. On the other hand, if the number of crops exported reduces, the nations importing these goods (Canada and the States) will suffer as prices for food increase because they are less accessible to us. See the dilemma?

ADdressing the challenge: no simple solution

We have a very confusing and frustrating problem on our hands. We can’t help one party without creating issues for another. What are we to do? Like I said before, compromise is key. The stakeholders in this issue need to get together and talk to find a solution. By stakeholders, I don’t just mean the fast food CEO’s, the politicians and the lawyers with the most power. I’m also talking about the community members, the small farmers, those most marginalized by the issue. We need to hear everyside of the problem before a solution can be made. In doing so, we can come up with new ideas that we wouldn’t have thought about if we didn’t have the experiences shared by Gary the farmer, or Sally the grocery store owner, or Jim the single father of three. Everyone needs to have their voice heard if we are going to solve this problem.

During the winter semester I had an amazing class called Issue Analysis and Problem Solving for Environmental Studies, led by Professor Sarah Wolfe. She had very interesting, well-rounded views on the field of environmental studies and taught me so much about what it means to solve a problem. During one of her lectures, Professor Wolfe said something that has resonated with me to this day. The lecture for that day was focused on water issues around the world, but the statement she made applies to any issue, whether related to the environment or not. If we can solve one problem, we can solve them all.

Water issues, for example: we have too much water use in some areas in the world while other areas don’t have access to fresh, clean water. Food insecurity: too much food here versus not enough there. Deforestation: too many trees being chopped down, not enough native lands being left for ecosystems to thrive and community culture to carry on. War: one party has resources or power that the other does not, and each party wants it all for themselves. Do you see what I mean? All problems are all innately the same, with just a few tiny alterations in their appearance. Solving these problems is just a matter of getting everyone impacted together and ensuring that every single person involved has a voice. Only then can we start to overcome the issues plaguing our world today.

Final thoughts

Next time you’re at the grocery store, stop and think about how fortunate you are for where you live. Next time you go to throw out a piece of fruit because it has a bruise, ask yourself if it’s really worth it to throw out or if you could actually still eat it—chances are you still can. These are real issues impacting our fellow Canadians, as well as people all over the world. Everyone deserves access to safe, nutritious foods. If we all do our part, we can help make this happen.

If you enjoyed this post, I encourage you to check out these ones:

- The truth about farmers markets

- What is Community Supported Agriculture (CSA)?

- How to eat sustainably in the winter

- 5 easy, healthy and sustainable ways to eat well on a student budget

- What’s the deal with almond milk?

Until next time!

1 comment